Hay que leer este texto de Nils Muiznieks, publicado en… el New York Times. Europa te espía (en inglés).

Archivo de la categoría: Privacidad

(2008) Bruce Schneier: Inside the Twisted Mind of the Security Professional

Uncle Milton Industries has been selling ant farms to children since 1956. Some years ago, I remember opening one up with a friend. There were no actual ants included in the box. Instead, there was a card that you filled in with your address, and the company would mail you some ants. My friend expressed surprise that you could get ants sent to you in the mail.

I replied: «What’s really interesting is that these people will send a tube of live ants to anyone you tell them to.»

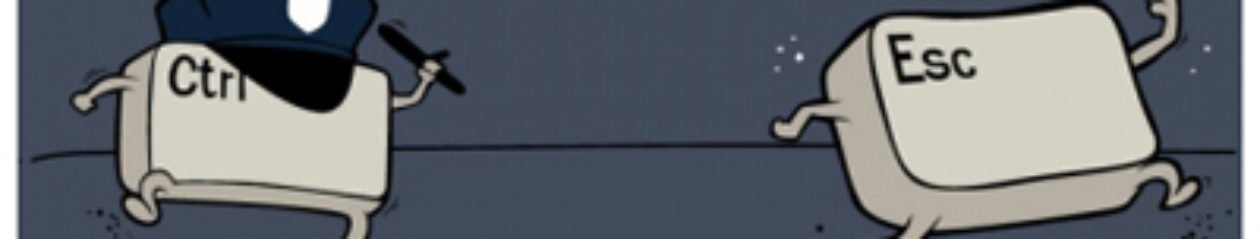

Security requires a particular mindset. Security professionals — at least the good ones — see the world differently. They can’t walk into a store without noticing how they might shoplift. They can’t use a computer without wondering about the security vulnerabilities. They can’t vote without trying to figure out how to vote twice. They just can’t help it.

SmartWater is a liquid with a unique identifier linked to a particular owner. «The idea is for me to paint this stuff on my valuables as proof of ownership,» I wrote when I first learned about the idea. «I think a better idea would be for me to paint it on your valuables, and then call the police.»

Really, we can’t help it.

This kind of thinking is not natural for most people. It’s not natural for engineers. Good engineering involves thinking about how things can be made to work; the security mindset involves thinking about how things can be made to fail. It involves thinking like an attacker, an adversary or a criminal. You don’t have to exploit the vulnerabilities you find, but if you don’t see the world that way, you’ll never notice most security problems.

I’ve often speculated about how much of this is innate, and how much is teachable. In general, I think it’s a particular way of looking at the world, and that it’s far easier to teach someone domain expertise — cryptography or software security or safecracking or document forgery — than it is to teach someone a security mindset.

Which is why CSE 484, an undergraduate computer-security course taught this quarter at the University of Washington, is so interesting to watch. Professor Tadayoshi Kohno is trying to teach a security mindset.

You can see the results in the blog the students are keeping. They’re encouraged to post security reviews about random things: smart pill boxes, Quiet Care Elder Care monitors, Apple’s Time Capsule, GM’s OnStar, traffic lights, safe deposit boxes, and dorm -room security.

The most recent one is about an automobile dealership. The poster described how she was able to retrieve her car after service just by giving the attendant her last name. Now any normal car owner would be happy about how easy it was to get her car back, but someone with a security mindset immediately thinks: «Can I really get a car just by knowing the last name of someone whose car is being serviced?»

The rest of the blog post speculates on how someone could steal a car by exploiting this security vulnerability, and whether it makes sense for the dealership to have this lax security. You can quibble with the analysis — I’m curious about the liability that the dealership has, and whether their insurance would cover any losses — but that’s all domain expertise. The important point is to notice, and then question, the security in the first place.

The lack of a security mindset explains a lot of bad security out there: voting machines, electronic payment cards, medical devices, ID cards, internet protocols. The designers are so busy making these systems work that they don’t stop to notice how they might fail or be made to fail, and then how those failures might be exploited. Teaching designers a security mindset will go a long way toward making future technological systems more secure.

That part’s obvious, but I think the security mindset is beneficial in many more ways. If people can learn how to think outside their narrow focus and see a bigger picture, whether in technology or politics or their everyday lives, they’ll be more sophisticated consumers, more skeptical citizens, less gullible people.

If more people had a security mindset, services that compromise privacy wouldn’t have such a sizable market share — and Facebook would be totally different. Laptops wouldn’t be lost with millions of unencrypted Social Security numbers on them, and we’d all learn a lot fewer security lessons the hard way. The power grid would be more secure. Identity theft would go way down. Medical records would be more private. If people had the security mindset, they wouldn’t have tried to look at Britney Spears’ medical records, since they would have realized that they would be caught.

There’s nothing magical about this particular university class; anyone can exercise his security mindset simply by trying to look at the world from an attacker’s perspective. If I wanted to evade this particular security device, how would I do it? Could I follow the letter of this law but get around the spirit? If the person who wrote this advertisement, essay, article or television documentary were unscrupulous, what could he have done? And then, how can I protect myself from these attacks?

The security mindset is a valuable skill that everyone can benefit from, regardless of career path.

Quantified self en manos de tu jefe, no es una buena idea

Ojo, que por aquí nos viene un peligro más que evidente de control del individuo por parte de su empleador, siempre a favor del segundo.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-08-12/wearable-biosensors-bring-tracking-tech-into-the-workplace

Ojo, yo uso wearables para auto controlar mi estrés y saber retirarme a tiempo de una reunión / conversación que le esté haciendo daño a mi mente y a mi cuerpo. Estoy muy lejos de ser una neo ludita. Pero estas tecnologías en manos de los empleadores son para tratar a los empleados como «recursos humanos» y optimizarlos a corto y tirarlos a la basura cuando se rompan.

Mucho ojo, por tercera vez.

Diálogo con Cory Doctorow en el Centro de Cultura Contemporánea de Barcelona

El sitio donde había que estar el miércoles pasado a las 19 horas era el @cececebe de Barcelona, en la cuarta planta, sala Mirador. Un espacio que hace honor a su nombre con chorros de luz natural y vistas a las cúpulas y las azoteas que coronan el barrio del Raval. Una sala horizontal, con pocas filas de butacas muy alargadas que rodean un pequeño escenario. La intención es potenciar la proximidad abrazando, no asfixiando, al presentador.

¿El motivo para estar allá? La charla con Cory Doctorow que forma parte de Kosmopolis.

Cory está sentado en el alféizar del ventanal, conversando animadamente con todo aquel que quiera acercarse a saludarlo. Por pura casualidad acabo de ver The Internet’s Own Boy. Pese haberme leído casi todas sus obras de ficción y tenerlo presente a diario por obra y gracia de su timeline de Twitter, nunca se me había ocurrido buscarlo en youtube, vimeo, etc., así que hasta hace apenas una semana no tenía ni idea de cómo habla, cómo se mueve, cuál es su presencia más allá de la foto tamaño DNI que decora la contraportada de sus libros. Si digo que es «igualito que en la peli» me pareceré a mi sobrina Andrea, que es fanática de One Direction, pero es cierto, y yo me fijo en, aunque no me dejo guiar por, esos detalles (mi sobrina Andrea tampoco). Su imagen está muy pulida: camiseta pirata, recién afeitado, corte de cabello de cepillo, calcetines de rayas de colores, zapatos veganos. Habla informalmente sobre montones de cosas a la vez. Me llama la atención la conversación sobre algoritmos de «profiling» con sesgo. Menciona en lenguaje comprensible para todos algo que los que saben de calculo numérico o machine learning identificarían como una función de optimización que converge, e inmediatamente se pone a diseccionar las implicaciones sociales de dicha propiedad matemática: si los polis creen que los malos son los pelirrojos, acabarán persiguiendo solamente pelirrojos. Mi mente dice, ¡wow!, ¡súper wow! y eso que la charla ni siquiera ha comenzado.

Cory es tremendamente inteligente y aúna una capacidad brutal de reflexionar y de aunar conceptos aparentemente inconexos con la velocidad del rayo a la que habla un inglés agradable, claro y florido. Es un conversador nato muy acostumbrado a hacer asequibles conceptos muchas veces complejos o poco conocidos. Además es muy amable y considerado con respecto al público, a quien él trata como personas individuales que han decidido invertir su tiempo libre en escucharle. Incluso en medio de la charla, si se daba cuenta que le ibas a hacer una foto, te regalaba largos segundos hablando mirándote para que la foto te saliese bien, hacía contacto ocular con los que ocupábamos las primeras filas, etc.

Los cuarenta y cinco minutos de la charla pasaron en un instante. Hablamos de privacidad, de derechos humanos, de copyright, de utopías, distopias, el rol del escritor de ciencia ficción, de algunas de sus novelas (Little Brother, Homeland, For The Win, Makers, Pirate Cinema) y de la recién publicada novela gráfica In Real Life. En el turno de preguntas estableció un curioso criterio (preguntas alternadas de hombres y mujeres, cualquier persona que se identifique con otro género puede participar en cualquier momento). Se acaban las preguntas. Pasamos al «mingling». Los que queremos lo saludamos, le damos la mano, las gracias, él nos regala sonrisas, comentarios siempre atinados, autógrafos y selfies. Por las caras del resto de asistentes intuyo que se van a casa tan felices como yo.

Tan feliz salí, que tras 10 años publicando en este blog, mi encuentro con Cory Doctorow es la efeméride que marca la primera vez que aparece mi cara aquí

Una mala idea: galletas físicas

En Helsinki han estado probando esto: un llaverito RFID que sirve para que las tiendas «sepas que estás en ellas» y te ofrezcan descuentos a la hora de pasar por caja.

La analogía es a las «cookies» de la navegación web.

Internet de las cosas y privacidad

Buena lectura sobre el tema en The Verge (en inglés).

Si estas empresas con información personal fueron vendidas por tanto… ¿cuánto valen tus datos?

Hoy en Twitter me he encontrado con este gráfico: «famous tech acquisitions, cost per user» (compras notorias de empresas de tecnología, coste por usuario)

Aparte de cosas que sucedieron durante el burbujón dot com de principios de siglo (compra de Geocities), este gráfico es interesante.

Si Google pagó 111,11 dólares por cada usuario de Flickr, ¿cuánto dinero espera ganar con las fotos de cada usuario? ¿y por la información contextual sobre el usuario que proporciona cada una de esas fotos?

Da qué pensar.

Google compra Nest, un par de buenas lecturas al respecto

Google ha comprado Nest, una empresa de «domótica/internet de las cosas» muy prometedora. Implicaciones de privacidad, consecuencias de darle toda tu información contextual a Google, que ya gestiona toda tu vida digital, más tu vida móvil si usas dispositivos móviles con Android (¡qué difícil decir que no a Google cuando quiere que te autentifiques!), pues muchas.

Vale la pena leer este par de recursos:

- Entrevista al CEO de Nest, en Fortune.

- Google, «Data über alles» y la sociedad de control, artículo de Versvs.

Comentario pragmático del día: Si no quieren estar monitorizados 100% del tiempo: No dependan de Google, no se instalen cacharrería en casa que envíe información a Google. Es difícil pero vale la pena intentarlo.

La Indie Web gana adeptos (aunque desconozcan el proyecto)

La Indie Web gana adeptos (aunque desconozcan el proyecto). Aquí el ejemplo de un abogado fastidiado por perder datos de su iPhone debido a una avería en su teléfono que pide una «nube personal».

Recomendamos releer este pequeño post sobre la Indie Web que publicamos hace unos meses.

Buenos días Corea: las dos caras de la moneda de la hipertecnificación

Vale la pena leer esta carta de un lector de La Vanguardia, Víctor Camprubí, sobre cómo ha cambiado Corea desde los Juegos Olímpicos de 1988, y sobre los nuevos cambios en temas de control. ¡Da qué pensar!